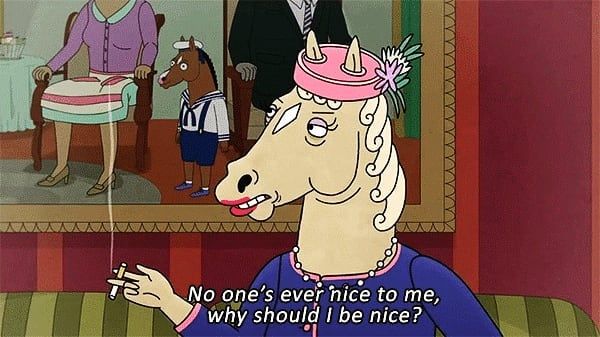

An adaptation of BoJack Horseman’s episode ‘Free Muffin’, some thoughts from the not so grieving widow Beatrice Horseman

Judy from supper club stopped by earlier today and told me all about her overly zealous children, about how her help is no help at all, and then all about how that husband of hers works too much, drinks too late, and flirts with too many young women. She covered her mouth in faux shock and said, ‘oh, how thoughtless of me!’ Which is of course just like Judy. She’s always going out of her way to be spiteful and petty.

Of course, I might be spiteful and petty if I had put my body through the trauma of having children past the age of twenty-eight. Does she think she’s a breeding cow? I just think she’s a cow.

Obviously, I didn’t say a word to Judy about her awful behaviour because then I would be the hysterical bitch. I’ve found that the high road suits me, and I it. So, I said, ‘how can I help you, Judy? Bear in mind that I do have a busy day ahead of me.’ That and a tap of my foot; I thought that surely ought to hasten her.

She was still smiling her witches grin. She bakes a lot for her boys, makes treats for the school’s bake sales. I can tell from her teeth and figure that she samples too much of her own stock. When she came by, she told me she had brought me a muffin. She normally shifts those little rocks for two dollars each, so giving me one today was probably all of the kindness that empty space in her ribs could muster.

No one mentioned to me before that when one’s husband dies one receives a free muffin.

Before today, Judy had only sour words and scathing looks to give me, but today she gave me a muffin. Because my husband died.

Now I suppose I ought to rehearse this eulogy, mustn’t I? Sit, Bella, and listen. If you listen to the wholespeech you can have tomorrow off as well as this afternoon. Anyway, I’ll only want to come home this evening and drink until sleep takes me. And no, spare me the pretence of your wanting to come to the funeral – we both know he was a bastard, from his bones, in his blood, out through his pores. Yes, I know he snuck you some of my good chocolates and called you beautiful and darling, but still, he was a bastard. I hardly want to go myself but of course, obligation dictates that I must. Count yourself lucky that all you have to do is listen for a few minutes, Bella. Life must be so hard for you.

Well, let’s begin: my name is Beatrice Horseman and my husband Butterscotch Horseman is dead. Spare your applause, Bella, don’t be pathetic. Let’s see now. Butterscotch, born in 1938, was a poor lover and a worse writer, ha! Now of course I can’t say that in the eulogy. Though, he’ll hardly care. Being dead and all.

No. Butterscotch wanted to be a novelist but ended up working for my father’s factory. I’m an heiress, you know. To a sugar company. Sugar, the world’s sweetest trade. That will keep me well-oiled and well fed until the day I die. I hardly needed a husband, but I was pregnant and unmarried in the sixties – it was either a husband or convent.

I’m kidding, Bella, don’t look so shocked. If my father knew I was pregnant before I was wed, he would have carried out a sensible, practical solution: a punch to the gut and some strong liquor. Now sit down and stop that weeping, Bella! It’s a joke. My god.

I’ll be serious. Butterscotch wanted to be a novelist his whole life, and a year before he died, he finally published his novel. Now, I haven’t read it, but bully for him. He carried out his life’s greatest ambition and died shortly thereafter.

And some people don’t believe in fate. Well, there you have it: my husband finally accomplished what he had always wanted to and died.

Of course, his death was his own fault and arguably caused by the publication of that ridiculous novel. He died in a duel. Did you not know that? Well, Bella, he seemed always to be whispering in your ear, he always did like flirting with the silly young maids. If someone was going to tell you the details, it would have been him.

Now, he didn’t exactly die in a duel, but he didn’t not die in a duel either.

Finally, he had published his book, and was revelling in his achievement. All the whisky he drank, the cigars he smoked, my! It’s miraculous that liver failure didn’t get him first. But then, he found that there were no bookstores selling his opus, no newspapers reviewed it. He howled about it, made such a stink to everyone and anyone, and finally, one young writer from some local paper in god-knows-where reviewed it. Ha! They thought his book was satirical for how poorly written it was. When they realised it wasn’t a comedy, well, that review brought a tear even to my eye. The reviewer didn’t leave my husband a leg to stand on! He opened that paper and the reviewer breathed fire all over him, burned him black.

In retaliation, because my husband could never let anything go, he accused the critic of being the worse kind of coward: unmanly, devoid of any wit. He issued a statement that challenged anyone who didn’t like his book to a duel. My husband, the grown man, the father of my child, the novelist, in 2009 challenged a man to a real duel with real pistols. The reviewer didn’t accept the challenge, he must have had an ounce of sense about him. But the challenge was public, and anyone was welcome to accept. Some madman from Montana came across it, took him up on that offer and made his way here, to San Francisco, to duel at dawn.

The day of the duel came. My husband met that man, exchanged words and begun his ten paces. My husband stopped halfway through pacing, however, to ask the man if he had read the novel. In doing so he tripped and bashed in his thick skull.

Don’t look so shocked, Bella. We both knew he was a moron.

And that’s his legacy: dying for a book that no one read.

He left the house while I was still asleep. He’d snuck out of bed a million times before to go galivanting on midnight romps – I’d learned to ignore his creaking the bed as he escaped. This was different from the start, however: on his previous romps, he simply disappeared out of the door and into the air, then hours, sometimes days later, would rematerialize smelling of whisky, girls and questionable decisions. This last time was different because he didn’t just disappear – he left a note.

Here, I have it with me now: ‘B – I’ll be thinking of you, sweetheart. Yours, B.’

He left me notes when we first met. Of course, we had little time to court. I was pregnant just hours after meeting him. We got a house together and he left notes around there for me. Then the baby came and there were no more notes.

Nothing filled me with more butterflies than those notes, when we were in love. I’d find them under pillows, on the fridge, in glasses – anywhere, everywhere. I know he flirted with you Bella, you may have felt that attention on your skin, warm like the summer’s first rays, but those notes filled my bones with a galaxy’s worth of suns and all of their heat.

Then, all these years later, he left me this last note. An Indian summer.

It was just like him to tease, to play the kitten with me, a ball of yarn. Sometimes, when we didn’t love each other but still had a child to raise, he’d say something profoundly tender, or press a hand on my thigh. When I smiled or touched him, he’d laugh. Laugh not like a joke was funny, but it was funny that I had misunderstood the joke.

So, it’s just like him, then, to leave me something to wake up my sleeping heart, and then die.

He’ll never tease me again. I hated the teasing, but those miniscule moments before his braying laughter, those moments where I thought I was a loveable thing, those were some of the best moments of my life. It’s been so many years but, in my chest, I can still feel that hot, violently fluttering feeling. Like we’re still young. After years of emotional neglect, my poor heart managed to feel it when I saw the little note that morning. My last ever note.

My husband is dead, and everything is worse now.

Now, I’m not sure how much of that I’m going to include in my real eulogy, but I’m thinking of something along those lines.

Oh, look outside – it’s BoJack’s car. My son’s car, Bella. He’s here already. A little early, that’s not like him. Hm, yes, I suppose he’s handsome in a washed up, looks like he hasn’t slept in four weeks sort of way.

He thinks that I’m the worst mother in the world. That’s why you haven’t met him, because he thinks he has no business visiting the world’s worst mother. Some may say a visit made out of pity is better than no visit at all, but the women who say those things are overly sentimental. Those tragic women.

And look at that: he smokes to much. He can’t even get out of the car without a cigarette. Goodness, Bella, you’d think he’d have learned from some of my mistakes, no? I used to be a fabulous singer when I as younger, his age even, and then one cigarette too many destroyed that. If he insists on shaming me by earning a living through dishonest means like acting, well, he may as well covet a fine voice to do so with.

You know, I haven’t eaten and now that he’s here I won’t have time to before the funeral. I think I’ll have Judy’s muffin. Hmph. My husband is dead and all I got was a free muffin. And it’s a little stale. It’ll have to do, I suppose.

Why doesn’t he get out of his car? Look at him in there, wasting time. If I want to see my son, I have to go to him. Every time. He’ll go months without seeing me, so I’ll have to hire a cab and make that horrible journey to Los Angeles to see him. He makes his own mother, a widow, go all of that way to that putrid city. It takes an hour to drive a mile, what with all that traffic, you know. What a waste of time, and it’s not like I have a lot of that left! He should appreciate that now, after the death of one parent. And still, he’s in that car, wasting both our time.

Ha! I should start inviting him to my supper club parties again. He used to love them when he was a boy. I used to have him sing the Lollipop Song. He acted like he hated it but then he’d get up before me and all of my friends (he loved attention, from women in particular), and sing with all of the heart and soul his little body could muster. He was never the best singer, but I’ll admit that it was a joy to see. He’d smile while he sung. I never really saw him smile. Of course, puberty had him decide he was too much of a moody brat to enjoy it anymore, so he stopped. But when he was small, he loved those parties.

My husband never joined in, but he loved my act. Yes, Bella, BoJack wasn’t the only talent in the family. I was a dancer when I was young – younger than you, even. Before the novel was finished, my husband spent all of his time writing and scrapping, writing and scrapping. He took the occasional break to rage about how the book wouldn’t finish itself; you should have seen the mental gymnastics he’d do to convince himself that myself and BoJack were somehow at fault for delaying his novel’s success. If only he knew how successful it would be.

Anyway, my husband spent most of his time seething in his study, until he heard my music. I’d start our old stereo, play my favourite dancing song, and take my place before the supper club. Just before I began, I’d peak the door creaking open, catch a sneaky eye. By the time I was finished, the door was wide open, and he’d be in the frame, arms crossed, looking like a bolder. He was hard as stone in everything but his eyes – they were soft. There was something in there, something akin to admiration. I tried to tell myself it was love, but that was a foolish thought for a younger woman.

While I danced, we’d all be there. The whole Horseman family. My son on the couch, wedged between to faux friends of mine who thought him a sweetheart. My husband, in the doorframe, pretending to feel nothing. And me, all legs and hair, rhythm and music; flying. That was family time, when we forgot the strangers that filled our home. I felt my boys and I’m sure they felt me, in our souls.

The three of us, we spent our lives on a carousel, spinning far too fast, consumed by dizziness, nausea and disgust. There would be moments in the revolutions where we’d lock eyes with each other, and that contact would ground us, steady us in the turmoil.

And then that eye contact would break. Holding it for too long, for too many seconds, well, that was far too much intimacy for any of us to handle. So, we broke that contact and the dizziness, the nausea, the disgust – it all came crashing back to us. Still, I haven’t decided if all of that is better or worse than those four pleading eyes, those windows to broken souls.

I know those souls are broken because of how oddly and cruelly they act. BoJack is still in his car and – how long has it been, Bella? Ten minutes? Ten minutes and he’s just been sitting there, staring ahead at his steering wheel. Does he know I can see him? And his father was broken. One has to be broken to be as cruel to leave their wife a note like he left me before he died.

It wasn’t until four years after BoJack was out of the house that I started to feel like myself again – less like just a mother. Of course, by the time he did leave, I was on the verge of forty and my best days were behind me. Even if I did leave his father, no one would have me. After those years, I got the teenaged stink of despair and apathy and disdain out from my cushions. For weeks those odours hung in the air like dust that couldn’t be sucked out by open windows. They dissipated eventually, and I filled my house with scents of roses and lemons and me. My husband was kind enough to limit the smell of vitriol to his own office. I may turn that office into a guest room or a library. Fill it with fragrances of old books, with crisp pages, good leather and fresh tea. The smells of peace. God knows my husband didn’t know peace, by scent or otherwise.

I still can’t stop thinking about his note.

After all these years, the way he writes hasn’t changed. Those B’s are the exact same as they used to be. Though, he used to address me as ‘Bea,’ with the E and the A. I wonder why he changed that?

Now, why are you crying Bella?

Bella?

B-ella.

You’re a dirty whore, you know that?

I saw this on the Bojack Horseman page on Facebook. At times reading it, I almost forgot it was fan-written and not something by the actual writers. Great job, and I wish you the best of luck on the creative writing assignment.

Glance through it for a couple of typos before you turn it in. One of the paragraphs in the beginning you say something about taking the high ground. You meant to say “I took it” but you said instead “I it”. There was also a too, two, and to error somewhere, but I don’t remember where. Other than those mild polishings, this is fantastic. Thank you so much for sharing

Will you have Beatrice notice the double entendre in the note?

‘B – I’ll be thinking of you, sweetheart. Yours, B.’ — thinking of her…

As the one he will shoot.

It’s brilliant; like “ICU / I see you”